|

The Mind-Body Connection

Mind/Body Medicine | The Stress Response | The Relaxation Response

Somatic Psychotherapy | Psychotherapy & the Brain |

Psychotherapy & the Nervous System

Mind/Body Medicine

What is the Body? Where is the Mind?

If you were asked to point to your mind, you would most likely point to your head, thinking that where your brain is. However, you would be wrong to think that your mind is limited to your brain alone. The mind exists throughout the physical body, mediated by the neurons and biochemicals of the central nervous system and the hormones of the endocrine system. The mind receives its impressions of the world primarily through the sensory system of the physical body (ie., the five senses of sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch) and interprets these perceptions through the brain.

Conscious thought is just one aspect of the mind, facilitated by higher brain functions. The unconscious mind exists in the lower brain functions, and is expressed in dreams, automatic reflexes, conditioned responses, somatic memories, and sometimes, in physical symptoms and behaviors.

What is a "Mind/Body Split"?

Western or allopathic medicine inherited the Greek Gnostic philosophy and practice of drawing a separation between the physical and spiritual aspects of human experience. This distinction remains with us today, in the arbitrary and stigmatized distinction between medical and mental disorders, and the exclusion of psychiatry and psychology from full participation in medical care and insurance coverage. Once you understand that we do not have a single feeling, thought, or behavior that is not mediated by the physical body, you can no longer make this division. Life is foremost a somatic experience.

There is a force within that gives you life -

Seek that.

In your body there lies a priceless jewel -

Seek that.

Oh, wandering Sufi,

If you are in search of the greatest treasure,

Don't look outside,

Look within, and seek that.

- Rumi

printable version |

When we speak of individual pathology, a "Mind/Body Split" occurs in various ways:

- When we feel that the body is not performing to the mind's expectations or demands, such as when we are trying to recover from an accident or illness, and progress is slow, or we are trying to accomplish some physical challenge, as in sports or dance. In these cases we feel that the body is not performing to our will, and it can become the target of our anger.

- During physical trauma, including medical procedures. In instances of overwhelming shock or pain, we can numb out and dissociate, having the sense of leaving our bodies for a while. Some individuals live in permanently dissociated states or feel numb in only certain parts of their bodies.

- When we are prevented from completing trauma or stress responses and discharging built-up tension in the body.

"Mind/Body Splits" are both a symptom of disorganized experience, and a cause of further dysfunction. Some typical symptoms of "Mind/Body Splits" are depression from internalized anger and helplessness; anxiety from the pressure of unresolved conflicts or negative emotions demanding attention; and numerous physical complaints. Because "Mind/Body Splits" cut us off from the internal resources of either the body or the mind, different aspects of our Selves cannot communicate and work together in the healing process.

Where do feelings exist in the Body?

Where do feelings exist in the Body?

Starting with psychoanalysis, the field of psychotherapy traditionally focuses on emotions: expressed or repressed in some fashion, conscious or unconscious. Yet what are emotions and what do they have to do with our health and well-being?

As modern science learns more about the brain and neuro-endocrine system, we are moving closer to understanding the bio-psycho-physiology of emotions. Most basically, emotions are mediated by the Limbic System in the brain, which includes a small area called the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus regulates all of our "appetites and drives" including the need and desire for sleep, food, sex, rest, etc, as well as our immune functions. Depending on the state of the body in the environment, the hypothalamus stimulates the pituitary gland, the master gland, to regulate the entire endocrine system. Thus, our thoughts, moods, behaviors and overall health are influenced by our emotions.

Feelings are psycho-physiological states of energy in the body. When you think about it, every emotional state has a corresponding physical tenor, a "felt sense" in the body. Anger is full of muscle tension in the jaw and limbs, ready for action. Fear is constriction in the stomach, chest and throat, along with some trembling. Joy is expansive in breath and movement. How would you describe your own various emotional energetic states? Try the "Color Your Feelings" exercise in the right column of this page.

Moods are more generalized feeling states. Whereas specific emotions are responses to situations and triggers, moods are more general and longer lasting. Anyone can have a temporary bad mood for up to a few days in response to negative events or news. Psychiatry becomes concerned about negative moods that last for two or more weeks.

When the wind blows,

that is my medicine.

When it rains,

that is my medicine.

When it hails,

that is my medicine.

When it becomes clear

after a storm,

that is my medicine.

- Anonymous

printable version |

In the brain, moods are regulated by biochemicals called neurotransmitters. Some of the most studied neurotransmitters are Serotonin, Norepinephrine, and Dopamine. The level of neurotransmitter in your blood stream can be influenced by your hormones, diet, exercise, exposure to stressors, environment, and heredity. Psychiatric medications do their work by targeting these neurotransmitters as well.

Even though feelings seem to be amorphous and ethereal, we do not have either feelings or thoughts separately from our physical matrix. On a practical level, I like the way Eva Marian Brown, MSW, describes the physiology of feelings in My Parent's Keeper: Adult Children of the Emotionally Disturbed:

Experience begins in our bodies. Many people find this a surprising thought, but a feeling is a physical event. Just as you feel physical pain when you put your hand on a hot stove, emotions, too, are physiological events. For example, we know that crying involves tears and sounds and changes in breathing patterns. Also, when someone is suppressing a strong feeling, like the need to cry, it takes a physical effort to stifle that feeling. If you try very hard not to cry, you may tighten a lot of muscles in your face and throat and restrict your breathing to hold back the tears. Or think about how your heart may have been pounding with fear when you stood up to give a speech, or perhaps suddenly your mouth go very dry.

In becoming sophisticated in noticing your feelings, the first step is to tune into what is going on in your body. When you ask yourself, "What am I feeling?" and you don't get a clear answer to that question, ask yourself, "What's going on inside my body?" Take an inventory. Notice what's going on with your breathing - Is it shallow or deep?; Is it rapid or slow? Are you aware of your heart? Is it beating slowly or fast? What is your temperature like? Are you sweating? Are you cold and clammy? Are you trembling? Is any part of your body clenched or stiff?

Some of your signals may be subtle. You might not find your heart racing furiously or your fists clenched. Instead you may notice a little bit of tightness in your throat, or your hands turning cold.

Over time, you'll learn to connect these sensations with feelings. For example, you may discover that you tighten up muscles in your neck and shoulders whenever your stomach knots up. As you begin to understand the vocabulary of your own body, you'll be able to move faster from the question, "What am I feeling?" to the answer, "I'm feeling angry" (or sad, or excited, or fearful). (pp. 48f)

What is Mind/Body Medicine?

Mind/Body Medicine recognizes

the complex interrelationship between

the mind and the body, maximizing

the functioning of both for their

mutual benefit. It is also called "Integrative Medicine" as it heals the

"Mind/Body Split" and is especially

useful when working with medical

conditions and illnesses.

How does Mind/Body Medicine work?

In general, Mind/Body Medicine

focuses on eliciting the body's inherent

Relaxation Response, as the natural

antidote to the Stress Response, in the process of healing.

The Stress Response

What is the Stress Response and how does it contribute to dis-ease?

What is the Stress Response and how does it contribute to dis-ease?

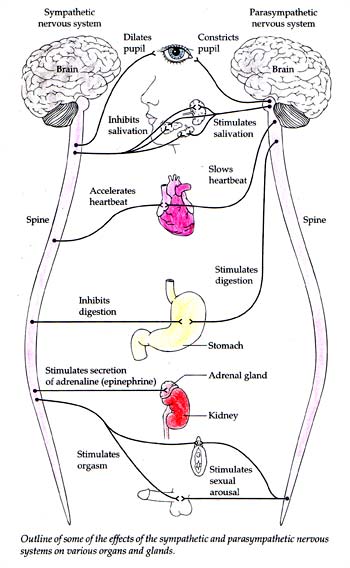

"The Stress Response" was coined by Dr. Hans Selye. Mediated by the sympathetic nervous system, it is the body's innate survival mechanism in response to perceived danger, also called the "Fight or Flight" response, divided into three stages: alarm (perceiving the danger); reaction (defensive action); rest and recovery. When our brain registers a threat, it triggers a series of internal reactions that prepare us for defensive action, either by fighting or fleeing. These changes include: an adrenalin surge to increase the heart rate, tense the muscles, and quicken the breath for action. After the fight or flight, the body then moves into a period of lower energy, for rest and recovery. These are incredibly adaptive changes when the danger is physical.

A problem arises, however, when the threat is mental: either a real mental stressor or an imagined one. Whenever the body/brain perceives such a danger, it engages in the same Stress Response and readies itself for defensive action when no action is necessary. When these responses are repeated throughout days, weeks, months, and years, without adequate discharge or rest, they accrue as physical tension in the body. Over time, this tension is expressed as both physical and mental symptoms.

When the Stress Response is not allowed to complete itself to the stage of rest and recovery, we are setting up conditions for dis-ease in the body. In the short term, this dis-ease can manifest as disrupted sleep, loss of appetite, poor digestion, lack of energy, low sex drive, etc. In the long term, this dis-ease can pervade more body systems and become organized into syndromes. Bowel disregulation can become Irritable Bowel Syndrome; breathing disregulation can become panic attacks; mood disregulation can become depression, etc. The condition of chronic stress in the body elevates cortisol, one of the body's stress hormones. Elevated cortisol is associated with insulin resistance, diabetes, and weight gain, as well as anxiety and depression. For more information on the effects of the Stress Response on health, look at Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers by Roberts Sopolsky, PhD.

What kinds of events trigger the Stress Response?

The Stress Response can be triggered by any perception of danger, whether it is physical or mental, real or imagined. Low level stress responses occur every hour, with an average of 50 such responses a day, including traffic situations, eating lunch in a rush, multitasking, running to catch a bus, etc. Higher level stress responses can be triggered by physical dangers and traumatic events, such as natural disasters, attacks and assaults, and accidents of various kinds. Even actions that are meant to be helpful can be experienced by the body as threatening when they induce fear or pain. These kinds of events include medical procedures.

The body reacts with the same stress response to psychological distress as it does to physical danger. This occurs whenever we recall a distressing event in memory, or anticipate and rehearse negative events in our mind. Other psychological stressors include over scheduling, work deadlines, conflicts with others, etc.

The more stress responses we have without recovery, the more vulnerable we become to further stressors. Over time, we tend to react more quickly than before to smaller triggers; and our responses can be bigger and last longer.

The Relaxation Response

What is the Relaxation Response and how does it contribute to healing?

The body has an innate Relaxation Response that acts as the antidote to the Stress Response. Mediated by the parasympathetic nervous system, the Relaxation Response elicits positive short term changes such as decreasing the heart rate; slowing and deepening the breath; relaxing the muscles. During the rest afforded by the Relaxation Response, the body repairs any damage from the Stress Response and recovers its sense of wholeness and balance. Over time, individuals who regularly practice the Relaxation Response have greater resilience to stress and trauma than others.

What are some techniques of Mind/Body Medicine?

Mind/Body Medicine uses a variety of techniques to bridge the Mind/Body Split when working with medical disorders:

- Breathwork

- Progressive Muscle Relaxation

- Body Scans & Autogenic Relaxation

- Guided Imagery

- Movement and Yoga

- Somatic Psychotherapies

Can Mind/Body Medicine be used with medical treatments?

Yes. When you are undergoing treatment for a medical condition, somatic psychotherapy is not meant as a substitute for medical treatment. Rather, Mind/Body Medicine is a complement to your medical treatments and can bring your entire Self into the healing process. It helps you work together with your care providers and engage more fully in healing and recovery. Best of all, you can share what you learn with others.

Numerous studies demonstrate that participating in Mind/Body Medicine can enhance medical treatment and improve outcomes. For example:

- Breast cancer patients who participate in support groups have longer periods of remission and better survivor rates.

- Women who participate in Mind/Body Groups for infertility have twice the rate of conception and pregnancy as women who do not receive the group support.

- Diabetes patients who learn to practice the Relaxation Response can lower their insulin dependence.

- Cardiac patients who learn to practice the Relaxation Response can decrease their need for anti-hypertension medications.

- Pain patients can reduce their reliance on pain medications with mind/body techniques.

Somatic Psychotherapy

What is Somatic Psychotherapy?

Somatic Psychotherapy is a form of Mind/Body Medicine that integrates the experiential levels of thoughts, emotions, and senses, and reduces the conditioned responses that persist as troubling symptoms.

How is Somatic Psychotherapy different from other psychotherapy?

Most talk-therapy does not engage the body, especially at the sensational and sensorimotor level. Somatic psychotherapy is a term for several treatment techniques that pay equal attention to physical responses, moving between the levels of thought, feeling, and sensation. When we feel "stuck" with a behavior or symptom, even though we understand it, somatic psychotherapy can move it. This is especially important in dealing with trauma responses.

What are some techniques of Somatic Psychotherapy?

Most talk-therapy does not engage the body, especially at the sensational and sensorimotor level. Somatic psychotherapy is a term for several treatment techniques that pay equal attention to physical responses, moving between the levels of thought, feeling, and sensation. When we feel "stuck" with a behavior or symptom, even though we understand it, somatic psychotherapy can move it. This is especially important in dealing with trauma responses.

Are there different schools of Somatic Psychotherapy?

Yes, there are a few schools of therapy that combine psyche (mind) and soma (body). Some of the better known ones are: Bodynamic Analysis; the Lomi School; Hakomi, and Integrated Body Psychotherapy (IBP). Some traditionally trained psychotherapists acquire additional training in somatics and integrate this into their work.

Can you use Somatic Psychotherapy if you don't have a medical problem?

Absolutely. Sometimes talking and insight do not produce the changes we are looking for. Most talk-therapy is left-brain centered, and depends on an accessible or conscious narrative (the client's story) for progress. However, sometimes a narrative is not available; the story may be partly or entirely unconscious. In these cases, it is necessary to engage the right brain in the treatment process. Several techniques of somatic psychotherapy such as art therapy, EMDR, and guided imagery and hypnosis, focus on right brain processing.

Psychotherapy and the Brain

What do the different parts of the brain contribute to psychotherapy?

The Right and Left Hemispheres The Right and Left Hemispheres

The foremost functional distinction in the human brain is probably its division into two hemispheres: the left and right hemisphere, each with functional specializations. The corpus caliosum separates the two hemispheres and connects similar parts in each hemisphere to coordinate processing. Typically, women have more connections between the two hemispheres than men, especially in the areas affecting verbal communication. Each hemisphere dominates the opposite side of the body. For example, the left hemisphere dominates in a right-handed person, and usually, vice versa.

Controlling the right side of the body, the left hemisphere dominates our verbal communication and narrative (story-telling) capacities; uses logical, rational, abstract thought and mathematical reasoning; and views time as linear. Left brain thoughts tend to be more optimistic than right brain thoughts. Hence, the left brain has been labeled "the masculine" side of the brain. This side of the brain is "turned off" in trance states induced by hypnosis.

Controlling the left side of the body, the right hemisphere dominates non-verbal communication and relies on "body language"; uses intuitive reasoning; is more spatial, rhythmic and connected with creativity and the arts; and views time as cyclical. Right brain thoughts tend to be more pessimistic and more dominant in women during the second half (luteal phase) of the menstrual cycle, when women also dream more. For these reasons, the right brain is associated with the feminine.

Clearly, except in very rare cases of the removal of a hemisphere due to uncontrolled seizures, we need the strengths of both hemispheres to function at our maximum capacity. Some vital aspects of our experience are stored in our left hemisphere (the narrative or plot line), while others are stored in the right hemisphere (our sensory perceptions, the body memories, our emotions). Somatic Psychotherapy accesses both hemispheres and enables us to integrate them consciously. We create new meaning of our experience through the interrelationship of thought, feeling, and sensation.

Left hemisphere oriented psychotherapy techniques include Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) and psychoanalysis. To learn more about "right brain" therapies, see Somatic Psychotherapies: Art Therapy, Hypnosis & Guided Imagery, Somatic Experiencing and Touch Therapy. To learn about therapies that coordinate right and left hemisphere functions, see EMDR and Journaling.

The Triune Brain

The Triune Brain

Another way of looking at the brain is through the different stages of human evolution: the Reptilian Brain; the Mammalian Brain (Limbic System); and the Primate Brain (Neo-Cortex).

Reptilian Brain - the brain stem and spinal cord. The Reptilian Brain is responsible for our most basic survival mechanisms, including mediating sensory perception and the sympathetic nervous system's "Fight or Flight" response to perceived danger. In resolving trauma, it is important to engage the defensive reflexes and actions triggered by the Reptilian Brain. Somatic Experiencing is especially useful for this level of processing.

Mammalian Brain - Like all mammals, human beings are emotional creatures. This basic function of the Limbic System fosters binding and attachment between mother and child, and empathy between other individuals. In humans, the hypothalamus, the primary gland for mediating emotions and immune functions, is contained in the Limbic System.

Primate Brain - The Neo-Cortex is the latest part of the brain to develop in humans. This "higher brain" functions to create and interpret meaning out of our life experiences, and is the center of our cognitive functions, such as thought.

Psychotherapy and the Nervous System Psychotherapy and the Nervous System

Through the spinal cord and the brain stem, the Central Nervous System (CNS) is like the main train terminal with lines to virtually every part of the body. Nearly everything passes through the CNS to get to its destination. A major component of the CNS is the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS), which governs body functions that are relatively involuntary and automatic, such as breathing and digestion. We don’t have to consciously think about breathing in order to breathe, nor do we have to order the gut to digest a meal that we are eating. These things happen automatically for us because of the ANS.

The ANS has two main “lines”: the Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) that stimulates functions associated with the Stress Response, and the Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS) which stimulates the Relaxation Response in the body. Negative thoughts and emotions elicit more uncomfortable SNS activation in the body: muscle tension, stomach constriction and poor digestion, holding the breath or shallow breathing, etc. Generally, when we experience these states, we want to change them to feel more comfortable. This is called self-soothing. Some maladaptive strategies would be overeating; using alcohol, nicotine, recreational drugs; hurting others; self-harm, such as hair pulling or cutting (these last behaviors elicit the PNS and release endorphins, the body’s natural pain relievers). Adaptive strategies are breathing exercises, yoga or physical exercise, meditation, hypnosis and guided imagery, journaling, cognitive restructuring, etc. Unconscious strategies for self-soothing would be some of the ego defenses, such as denial, sublimation, displacement, or intellectualization; or poor relationship dynamics, such as gossip and blaming others, etc. And yes, some people help themselves feel better by picking fights, yelling, or becoming physically aggressive.

Individual tolerance for SNS activation and negative emotional states varies from person to person. We develop this capacity from infancy onward. A mother is regulating her baby’s nervous system when she responds to its cries by holding it, caressing its skin, nursing or feeding, and making eye contact. When mother responds well enough and often enough, so that the level of discomfort doesn’t overwhelm her baby, the infant’s nervous system develops the capacity to regulate itself. Conversely, if a baby’s needs are neglected and the discomfort is overwhelming, the nervous system develops under disregulation and tolerance for negative states decreases.

Psychotherapy affects the nervous system in the same way the mother’s care affects the development of the baby’s nervous system. The relationship between the therapist and the client reflects the mother/child dyad. A somatic psychotherapist observes the client’s emotional and physical reactions, tracking the interplay between SNS and PNS states, and brings these to the client’s attention. Through practice, the client learns to track their own movement between these states, catching early signs of SNS activation and practicing PNS self-soothing early, before feeling overwhelmed and disregulated. Gradually, the client’s capacity to tolerate negative emotions without acting out increases; mood sings become less frequent and less intense, and client reactions are calmer, leading to greater containment and self-regulation.

|